Solving the Wrong Problem

(or why you shouldn’t believe things you know)

What you know that ain’t so

There’s a perspective that “it is better to know nothing than to know what ain’t so.”1 In my experience this is certainly the case with debugging because “knowing” will lead you down a rabbit trail of trying to solve the wrong problem.

The approach that works well for me is to “trust but verify” your knowledge. If your initial attempts to fix the bug in your code don’t work, take some time to check your assumptions – specifically your assumptions about where the bug is. This slows down your work initially because you’re often testing things that are behaving as you expect expectations, but this saves you from spending a lot of time trying to fix the wrong problems.

A recent example:

I’m writing a model that uses relationships between genes to predict a trait. The problem is that the model isn’t something I can write by hand (there are 6,067 inputs) and is way to slow – I’ve estimated it would take about 1.7 days to complete a single epoch (training cycle).

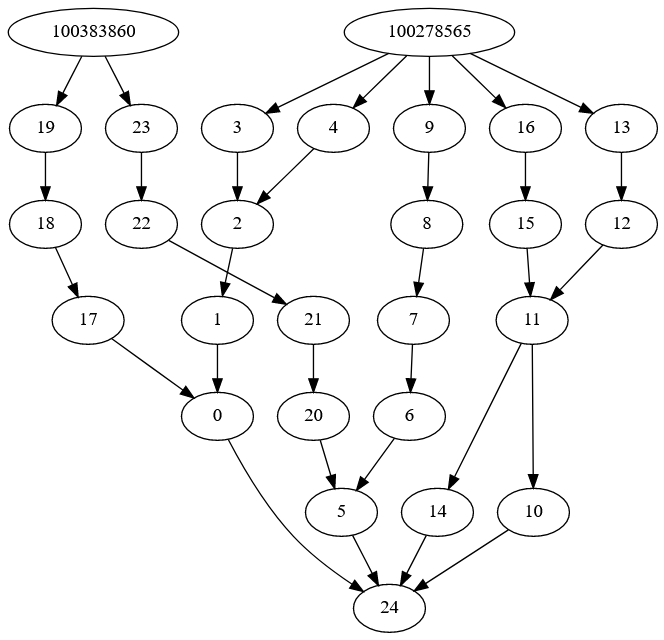

In the diagram above, data from each gene (the nodes at the top) is fed into different functions (nodes 0-23) representing associations between different biological processes until they reach the output node (24) which predicts the trait.

Some nodes share the same input (here node 14 and 10 both need node 11 as input). Under the hood I have the model storing the output of these nodes so it doesn’t have to re-calculate outputs un-necessarily (here the model would look-up the output of node 11 instead of recalculating it). This seems to work nicely but is a little unusual – in over two years this is the first time I’ve manually done this sort of thing.

Because of that, when I move my model from a tiny demo data set to the real thing and saw it was slow as molasses I “knew” my model slow because it was storing and retrieving intermediate results.

One assumption underlying this is that the model library is effectively designed and optimized such that it’s easier to get worse performance by doing unconventional things than better performance. This isn’t a bad assumption most of the time but we’ll see how it got me thinking about the wrong problem. My thought process went something like this:

“Okay, so I’m doing something a little unconventional by looking up module outputs. Maybe if I can rewrite the model without this, some ☆Pytorch magic☆ will happen improving training speed.”

“Hmm, the most straightforward way to write a model would be to chain the inputs and outputs like so”

input_1 = x_list[0]

module_2 = x_list[1]

intermediate_1 = module_1(input_1)

intermediate_2 = module_2(input_2)

output = module_3(nn.Concatenate([intermediate_1, intermediate_2], axis = 1))“But it would be unfeasible to do this because I’d have to write a line for each input and process 8,868 in total… or would it?”

This should have seemed like a totally unreasonable thing to do and been where I stopped to think if there was another way to get a speed increase (or tested this by writing a tiny neural net by hand with and without caching results and looked for a tiny difference in speed). However, years ago I met a class deadline by using python2 to write python2 code so this seemed perfectly feasible.

So the plan became :

Generate a boat load strings containing python code

Use Python’s

exec()andeval()functions to run each stringSit back and think about what a clever idea it was having my code write my code.

Several hours later I’ve learned a fair bit about how exec() and eval() handle scope and that their behavior between python2 and python3 has changed and still have no working model. So I decide to print the code I wanted executed to the console paste it (all 8,868 lines of it) into my model definition, and run it.

This solution was inelegant but quick to implement and exactly what needed to happen because the model didn’t perform any better. If anything it was slower, so there definitely wasn’t any ☆Pytorch magic☆ happening. This was a big enough surprise that it got me to question if the model was the problem after all instead of running down other rabbit trails.

So where’s the problem?

Building a model may be the most evocative part of the data science workflow, but the steps that precede it are often as or more important. Choices around how to handle missing or potentially unrepresentative data are important as are how data is stored and moved around. In this case, I wasn’t thinking about these critical choices.

For each individual, there are data for genes throughout its genome (x_list, a list where each entry is a gene’s SNPs), and it’s trait of interest (y). Here’s the (simplified) code for this data set:

class ListDataset(Dataset):

def __init__(self, y, x_list):

self.y = y

self.x_list = x_list

def __len__(self):

return len(self.y)

def __getitem__(self, idx):

# Get the data for index `idx`

y_idx =self.y[idx]

x_idx =[x[idx, ] for x in self.x_list]

# Move to GPU so model can access it

y_idx.to('cuda')

x_idx = [x.to('cuda') for x in x_idx]

return y_idx, x_idxDo you spot what’s happening? When __getitem__ loads an observation, it has to move data from each gene to the GPU. This process isn’t instantaneous and is happening for each of the 6,067 genes every time an observation is loaded.

Training a network with a mere 100 observations (batch size of 10) takes 101.89s/it but if all the data is moved to the GPU before its 15% faster at 86.34s/it.

That’s nice, but since there are over 80,000 observations, it’s not enough to make training this model feasible. There’s another place we can look for improvements, and that’s the batch size. Increasing the batch size will mean that more observations are being moved to the GPU at a time so it has to happen fewer times. In this example getting all training observations in a single batch makes training 86% faster at 13.44s/it.

Take home:

Testing your assumptions (especially while debugging) is like insurance. When you’re on the right track from the start, it’ll cost you a little time that you otherwise wouldn’t have spent but it’ll keep you from spending a lot of time trying to solve the wrong problem.

post script:

Even solving the right problem the result may not be what you want. Extrapolating from a more realistic subset of the data results in an estimated 5.6 hours per epoch. Better than 1.7 days, but not a home run .